Performance appraisal is a corporate procedure with a long history — and a reputation as a process neither employers nor employees look forward to. But it’s an indispensable tool, as employers have both the right and the responsibility to assess their employees to identify who’s doing well, who’s treading water, and who needs to improve.

It’s also helpful for employees — they deserve to know where they stand with their employer, and a performance appraisal can indicate whether they should be asking for a raise or promotion or making a plan with their supervisor to up their game.

Conceptually, performance appraisal is essentially fair and reasonable, but in practice, it can be a messy process. People are complex creatures saddled with a jumble of motivations and biases, and they often aren’t aware of them. That’s true for those who conduct the appraisals and for those they’re reviewing, so biases and vague, subjective metrics can often skew a performance appraisal.

A brief history of performance appraisal

People who work together always judge each other’s performance — it’s almost a reflex. And it’s been going on for thousands of years — long before anyone introduced the performance review, people in hunter-gatherer societies could easily pick out who was the best spear thrower or who could easily get a fire going.

Everyone got along fine with that level of performance appraisal for millennia — that is until the Industrial Revolution kicked into high gear in the 19th century. In 1881, Frederick Taylor, who’s known as the father of Scientific Management, started a series of time and motion studies to increase efficiency and productivity at the Midvale Steel Company in Philadelphia. Under Taylor’s direction, factory managers observed workers carefully to identify areas where they were wasting time or motion.

Although the studies helped Taylor achieve his goals, the changes he implemented created resentment among the workers, who began to feel like cogs in the system (which probably didn’t help either efficiency or productivity). Still, Taylor’s time and motion studies rationalized early factory processes and laid the theoretical foundation for the assembly line and mass production — and they served as an early method of judging employee performance.

During World War I, the U.S. Army created a system to track poor performers, likely making it the first organization of any sort to systematically conduct performance appraisals. By World War II, the military modified the process to help sift through the millions of draftees to find those who had the potential to be officers. By then, a majority of U.S. companies were using performance appraisals to award merit raises, bonuses, and promotions.

Understanding what really motivates employees

For decades, employers assumed their employees were motivated simply by their pay. So for a long time, they thought they could encourage some employees to keep up the good work by giving them raises and motivate others to improve by giving them a poor evaluation and suggesting they might lose their jobs.

Social psychologist Douglas McGregor challenged this assumption in his landmark book, The Human Side of Enterprise. In it, he argued that the biases individual managers had about people’s motivations influenced how they managed and evaluated their subordinates.

McGregor proposed two theories to explain this. Theory X managers, who tend to be tyrannical micromanagers, assume their employees work grudgingly and only because they need the paycheck. Theory Y managers assume their employees are intrinsically motivated to do well and take pride in their work, so they ask everyone to participate in making decisions and planning within the organization.

Pioneering psychologist Harry Levinson took the human factor in employee appraisal another big step forward in a 1976 article in the Harvard Business Review. He described how managers conducting performance appraisals can be fooled into giving good evaluations to undeserving team members who play office politics well while overlooking high performers who don’t have a lot of people skills.

“Some people develop political diagnostic skill very rapidly; often, however, these are people whose social senses enable them to move beyond their technical and managerial competence,” Levinson wrote.

He went on to explain that “some may be out and out manipulative charlatans who succeed in business without really trying, and whose promotion demoralizes good people. But the great majority of people, those who have concentrated heavily on their professional competence at the expense of acquiring political skill early, will need to have that skill developed, ideally by their own seniors.”

Levinson argued that it’s up to managers to cultivate what we now call “soft skills” in those competent employees who don’t naturally have them.

Performance appraisal in the contemporary workplace

The history of the performance appraisal is long and full of both good intentions and missteps, but the ultimate goal is to develop each employee’s potential — as well as improve the company culture and the bottom line.

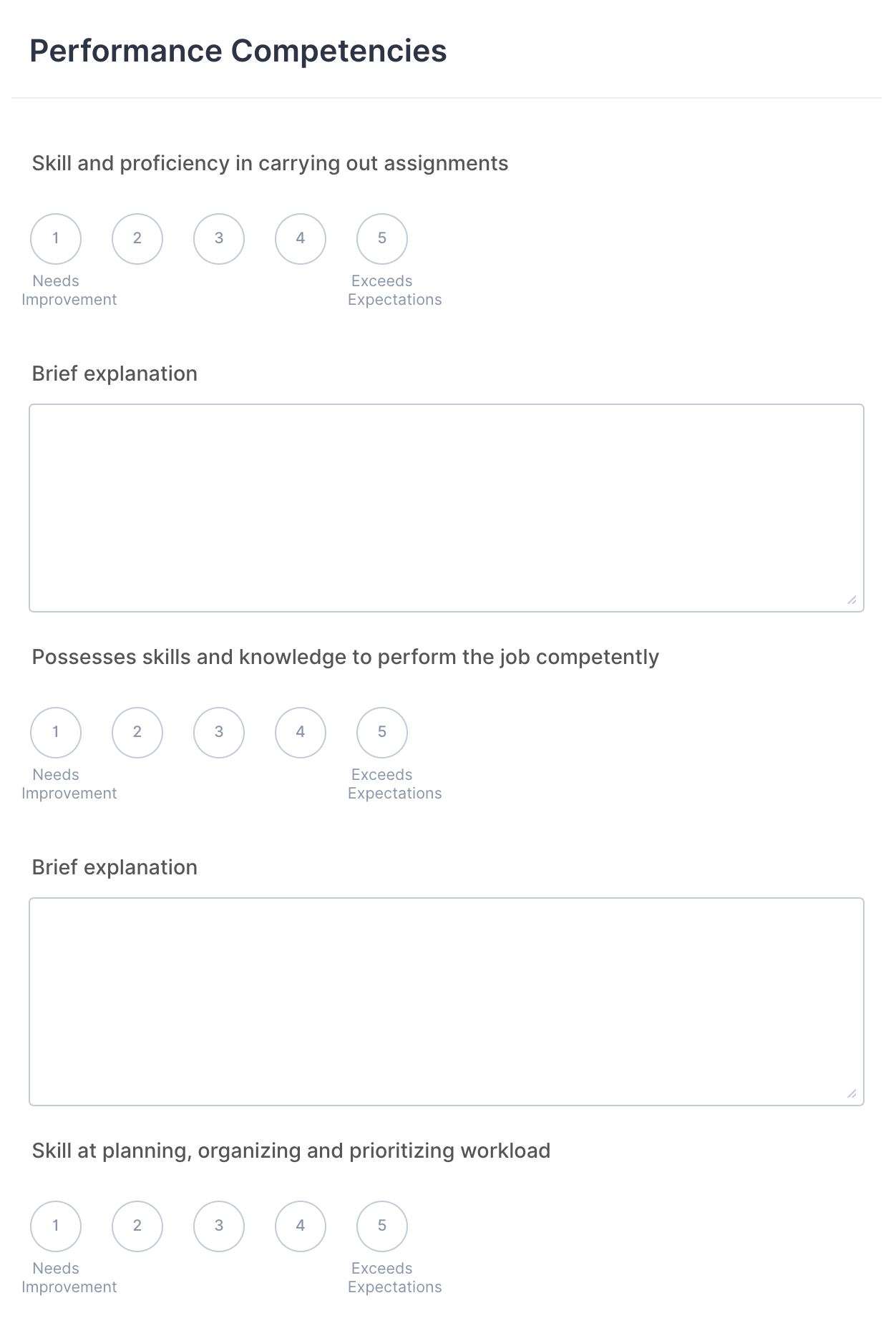

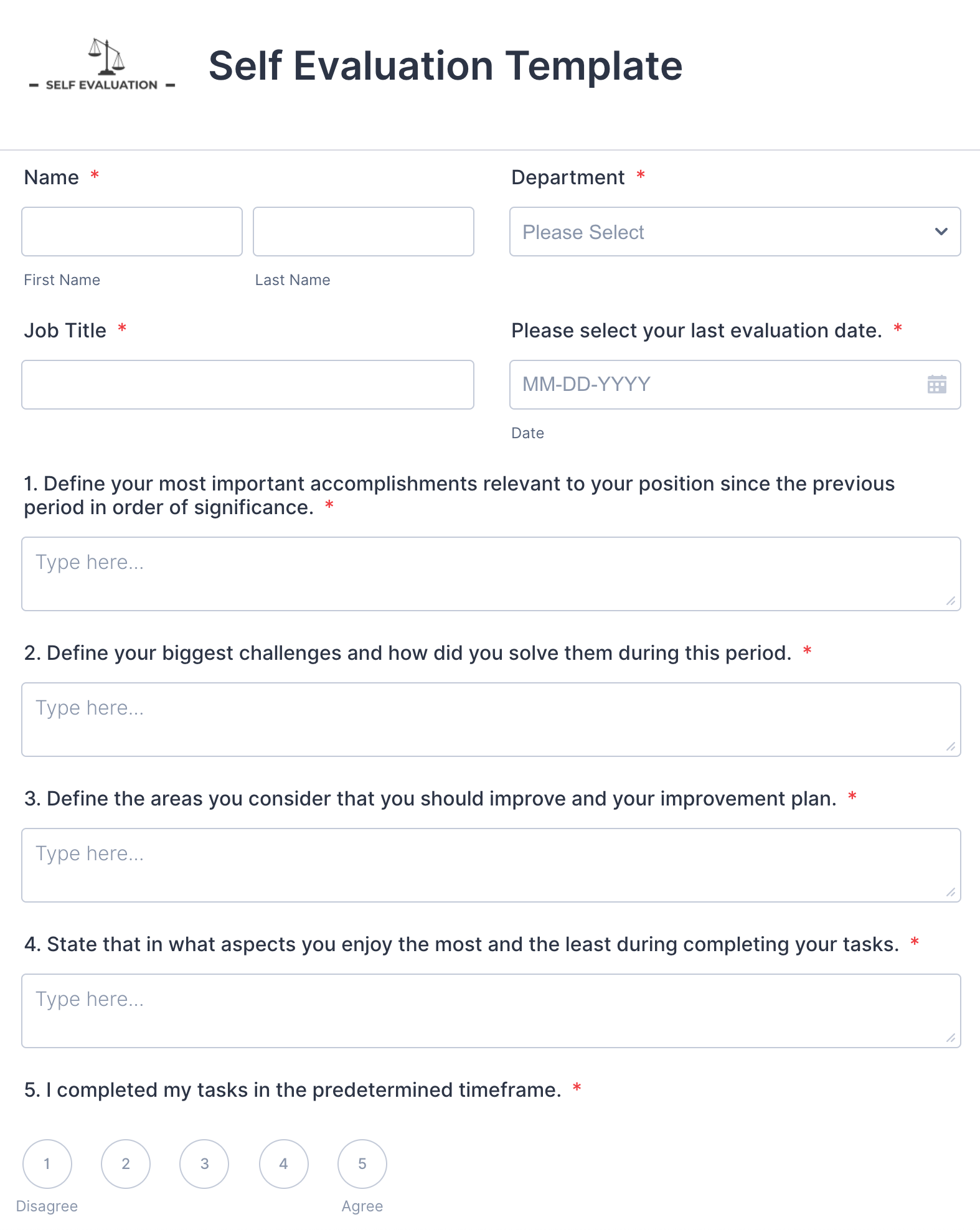

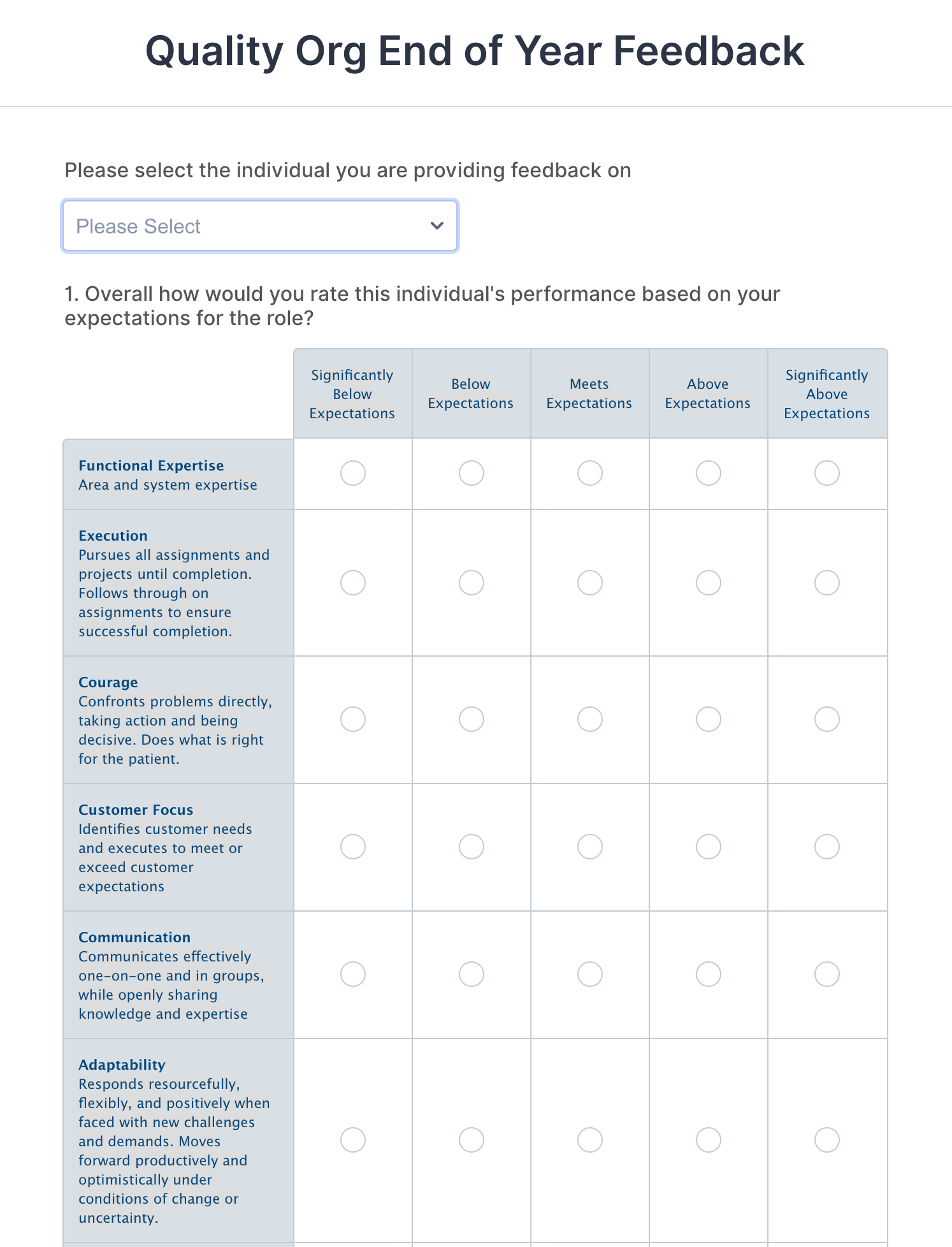

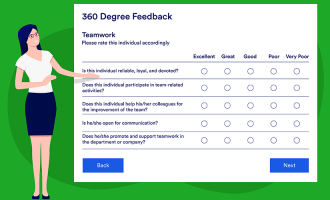

How can you make the process easier and more effective? Jotform offers dozens of templates that are ideal for designing a better employee evaluation process. You can customize these templates to give as much attention to how a person positively contributes to the team as you do to what they need to improve. And you can recognize their contributions to the company culture that don’t easily translate into numerical metrics.

It’s important to include these additional pieces of information — companies that only recognize and reward quantifiable results, without paying attention to how someone achieves them, can end up with “toxic superstars” who drive away good employees.

What Levinson wrote decades ago when arguing for a more compassionate and holistic approach to employee performance evaluation and workforce management remains relevant: “Performance appraisal needs to be viewed not as a technique but as a process involving both people and data.” So a good performance appraisal should meet these three objectives:

- Tell employees how the company views their performance.

- Serve as a blueprint for determining how the employee can improve substandard performance.

- Give managers a basis for future changes in assignments and compensation.

The workplace today is more likely the home office than the factory floor, and enlightened managers have come a long way since Frederick Taylor’s intrusive time-motion studies. But some things haven’t changed, and they probably never will. People will always dislike being micromanaged, and they’ll always respond better when leadership treats them as team members rather than entries in a ledger or a spreadsheet.

Successful companies recognize the importance of a performance appraisal process structured to both reward outstanding employees and improve those who are diligent but not superstars.

Send Comment: